Blog

Participatory Grantmaking: Power to the People

Participatory grantmaking at the Brooklyn Community Foundation

Nothing about us without us.

This declaration has become a rallying cry for the disability rights movement.*

It could just as well be a call to arms for participatory grantmaking — the practice of giving more power over philanthropic spending to the people that it is supposed to help.

So it’s no accident that the Disability Rights Fund, which calls itself a “grantmaking collaborative” between donors and disability rights advocates, is a leading practitioner of participatory grantmaking.

The Disability Rights Fund supports advocacy groups led by persons with disabilities, primarily in the global south. It puts persons with disabilities on its governing and advisory boards to help shape its strategy as well as to decide on specific grants.

“We’ve been trying to model the world as we want to see it,” says Diana Samarasan, the group’s founding executive director. The fund supports activists who reject a charity approach and assert their rights to steer their own lives, and so it makes sense to invite them to guide its work as well.

Has the time come for participatory grantmaking? It seems so. That question is the title of an excellent new report [PDF] commissioned by the Ford Foundation and written by Cynthia Gibson, a consultant and practitioner of participatory approaches. Gibson will follow up with a how-to guide on participatory grantmaking that GrantCraft, a unit of the Foundation Center, plans to release next year.

Participatory grantmaking fits this political moment: It reflects a populist distrust of elites and experts that, among other things, fueled the Trump and Sanders campaigns, as well as Brexit, anti-intellectualism, the idea of “fake news,” and the like.

Big private foundations are nothing if not elite. Those that fail to examine their decision-making practices face the risk of “being seen as part of the problem, rather than as the problem-solvers” they would like to be, says Chris Cardona, a program officer for philanthropy at Ford, in a blogpost about the report:

In this time of dramatic change, people are becoming distrustful of established institutions, including foundations, and are demanding greater accountability and transparency. Across sectors, elite-driven, top-down decision-making is increasingly viewed with suspicion, if not outright hostility.

Participatory grantmaking has support from the left, as you would expect: Practitioners tend to focus on social justice and human rights. The National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy hosted a webinar on the topic last summer.

Perhaps surprisingly, it appeals to conservatives as well. A thoughtful essay by Michael E. Hartmann in Philanthropy Daily begins with William F. Buckley Jr.’s quip that he would “rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University.”

Hartmann, a conservative, praises the Ford report as “a healthy and necessary dose of establishment-philanthropy self-flagellation.” While cautioning that participatory grantmaking creates risks as well as benefits, he writes:

All in all, Ford should be commended for proposing and starting an important discussion. Grantmakers on both the left and right should join the Ford-inspired debate.

True enough. But while participatory grantmaking is having a moment in the sun, the practice is being embraced mostly by smaller funders on the fringes of the philanthropic establishment. It’s especially appealing to human rights funders serving marginalized populations — disabled persons, LGBTQ or young feminists — who can be invited into a meeting room. The Amsterdam-based Red Umbrella Fund, for example, which serves sex workers, says, quite logically, that “sex workers themselves are the best positioned to know what is needed for them, and best placed to do something about it.” Foundations aimed at protecting the oceans or researching cancer are better advised to rely on experts in those fields.

Nor is participatory grantmaking a new phenomenon, as Gibson notes in the report. The Headwaters Foundation for Justice, a small foundation based in Minnesota (of course!), has been practicing what it calls “community-led grant making” for more than 30 years. Its website says it is guided by a “a simple and powerful truth: the people who experience injustice are essential to ending it.”

It seems probable that participatory grantmaking is not only the right thing to do but the smart thing to do. That said, it’s not easy to do. Questions abound: Precisely who gets to participate? What does “participate” mean, in practice? If grantees get to divvy up pools of money, how can funders guard against log-rolling or conflicts of interest? It’s all too easy to imagine participatory grantmakers getting bogged down in process.

“There are real costs associated with (participating grantmaking),” says Katy Love, director of community resources at the Wikimedia Foundation. “It’s beautiful and it’s amazing and it’s complicated and it’s messy.”

Then there’s the hardest question of all: Can foundation executives, with their stellar resumes and Ivy League degrees, be persuaded to share power with the less educated and less privileged? Gibson writes:

The culture change needed to make these practices part of the ethos of grantmaking organizations isn’t for the faint of heart; it can take years, if not decades, to root in a meaningful way.

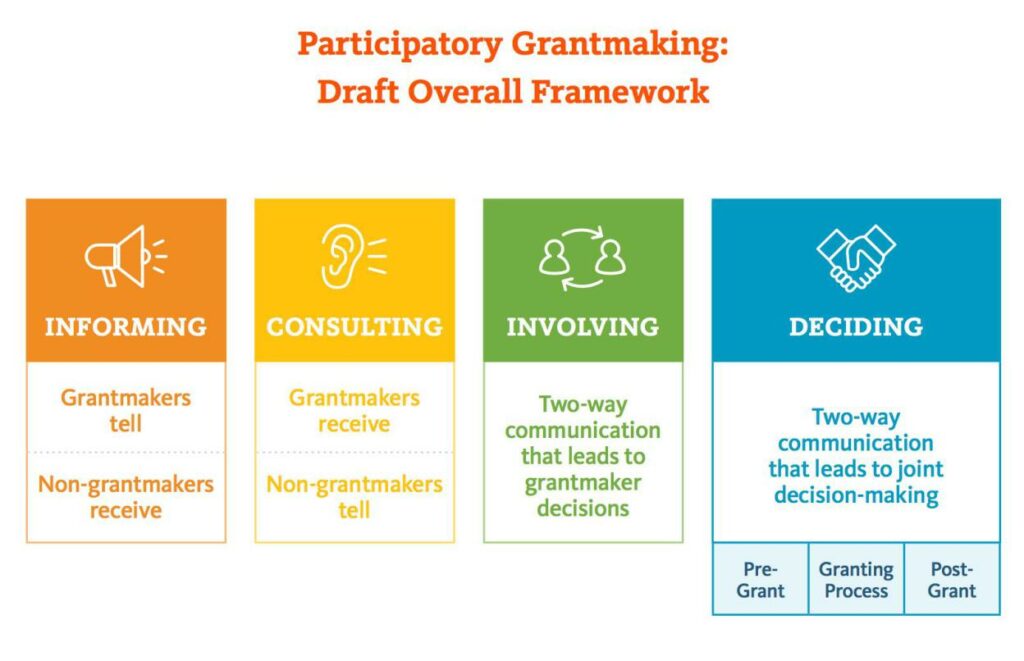

Her report provides a useful taxonomy of participatory grantmaking in graphic form. Old-style foundations (“informing”) work from the top down, others bring outsiders into the process to varying degrees (“consulting” or “involving”) and a smaller number share power with their grantees or beneficiaries (“deciding”).

Here are brief sketches of three funders who are pushing the envelope:

The Disability Rights Fund: The fund’s strategy is guided by a global advisory panel made up entirely of activists, nine of whom are persons with disabilities and three who come from other human rights communities, according to Samarasan. “They talk about where the movement is going, and how that should affect our grant making priorities,” she says. Four activists from that panel sit on a grant-making panel, along with four donors. Ultimate power rests with a nine-member member board, three of whose members are persons with disabilities and one of whom is a parent of a disabled person. It’s a lot of advice-soliciting for a small foundation that gives out $2m to $2.5m a year in grants, some for as little as $5,000. Funding comes from the Open Society Foundations, as well as the UK and Australian governments.

The Wikimedia Foundation: More than 70,000 volunteers added 5 million articles to Wikipedia in 2016, according to the foundation, which operates Wikipedia and other free knowledge websites. Just as anyone can become a Wikipedia editor, anyone who edits Wikipedia can make a proposal to the Wikimedia Foundation. Through a voting process, volunteers have “the power to make decisions” about many of the grants distributed by the foundation, says the foundation’s Katy Love. How that works is necessarily complicated, involved a staff process to review grant applications, virtual and telephone committee consultations and face-to-face meetings that lead to “what can be quite difficult conversations about how to use our limited resources to make the biggest possible difference,” Love says. Grants can go to individuals or nonprofits, and many aim to spread Wikipedia to the global south. Grants added up to about $11m last year.

The Brooklyn Community Foundation: Soon after joining the Brooklyn Community Foundation as president and CEO in 2013, Cecilia Clarke launched Brooklyn Insights, an effort that engaged more than 1,000 Brooklynites in conversations about the borough’s future and the foundation’s role. She then oversaw a community-led grantmaking effort in Crown Heights, a rapidly-gentrifying neighborhood of Hasidic Jews, West Indians and African-Americans. “It’s like time-lapse photography around here,” she says. “You are watching buildings going up in front of your eyes.” After a year of scattered grantmaking, and deliberations of an advisory board made up of neighborhood residents, the Crown Heights effort evolved to focus on public spaces. While the foundation’s board retains ultimate authority, it upheld recommendations from the neighborhood people, including one that challenged the plans of a real-estate developer who is a foundation donor. “It was a cultural shift,” says Clarke. “The residents lead this process.” The foundation explains how it all worked on this lively website.

What’s not clear is whether participatory grantmaking can improve the work of large global or national foundations, like the Ford Foundation. The concept aligns neatly with Ford’s belief that inequality is “the defining challenge of our time, one that limits the potential of all people, everywhere,” but if the foundation can’t find ways to share power as well as money with marginalized people, can it claim, as its does, that “addressing inequality is at the center of everything we do?” (Ford declined to be interviewed.) To its credit, Ford has made grants to intermediaries, including the Disability Rights Fund, the Red Umbrella Fund and the Global Greengrants Fund, which supports grassroots environmental advocates. The Novo Foundation and Open Society Foundations also support existing participatory grantmakers. By doing so, they are gently disrupting the power dynamics of conventional philanthropy.

—

* “Nothing about us without us” is the title of a book about disability oppression and empowerment by James Charlton, and another by David Werner, written by, for and with disabled persons. DRF’s board co-chair William Rowland also wrote a book called “Nothing About Us without Us” about the struggle for disability rights in southern Africa.